Question: Do farts have political implications?

Short answer: Yes.

Long answer: One of the most famous farts in history was issued by Henry Ludlow in 1607. Mr. Ludlow sat in the English House of Commons between 1601 and 1611, and in 1607, during the Speaker’s address, he farted loudly, triggering laughter from the House.

The fart was subsequently described in a poem called “The Censure of the Parliament Fart”, which begins as follows:

Never was bestowed such an art

Upon the tuning of a fart.

Downe came grave auntient Sir John Cooke

And redd his message in his booke.

Fearie well, Quoth Sir William Morris, Soe:

But Henry Ludlowes Tayle cry’d Noe.

Up starts one fuller of devotion

The Eloquence; and said a very ill motion

Not soe neither quoth Sir Henry Jenkin

The Motion was good; but for the stincking

Well quoth Sir Henry Poole it was a bold tricke

To Fart in the nose of the bodie pollitique

Indeed I confesse quoth Sir Edward Grevill

The matter of it selfe was somewhat uncivill

Thanke God quoth Sir Edward Hungerford

That this Fart proved not a Turdd [2]

The poem became very popular, with various people adding couplets well into the 1620s. As time went on and the poem grew in length, it became a forum for political commentary, with different couplets addressing taxes, trade, and particularly freedom of expression. In part, the writers were “farting in the face of Puritans” (O’Callaghan, 2006). This idea of using a fart as a vehicle for other kinds of intellectual exploration is an interesting one, but it does raise the question of what was so special about this fart.

In previous work, we have been able to unearth a fart that had gone unnoticed for the last 70 years. But can we reconstruct the lost Ludlow fart from 400 years ago? This is a greater challenge, as there is obviously no audio available, and in fact the House of Commons did not even keep written records of its proceedings at the time.

Nevertheless, we have the following facts:

- The poem describes the fart as a “very ill motion” that produced a “stincking”, suggesting that it was quite smelly. We know that smelly farts are louder and have lower sound frequencies. They are also shorter in duration than non-smelly farts.

- One contemporary politician, Robert Bowyer, wrote in his diary that the fart came from “the nether end of the House…whereat the Company laughing the Messenger was almost out of Countenance”.

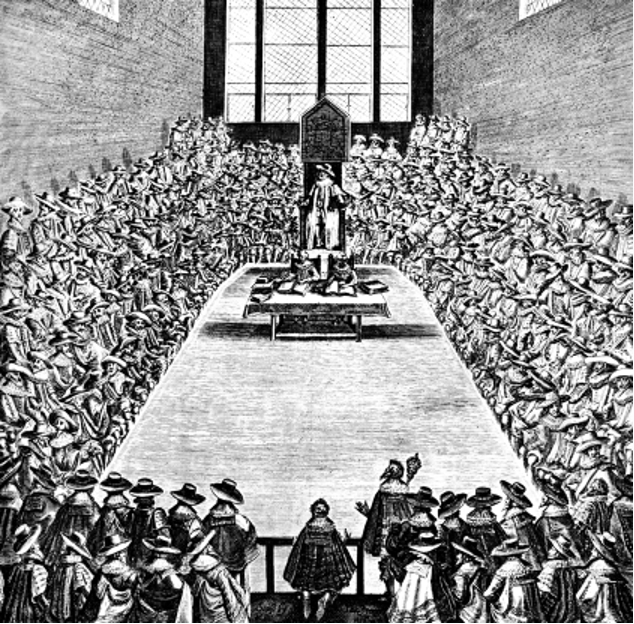

- In the 17th century, the Chamber of the House of Commons measured 10 by 17.5 metres, with a ceiling that was 14 m high.

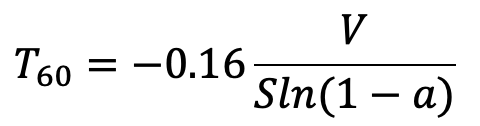

With this information, we can guess that the fart was brief, loud, low-pitched, and that it would have been affected by reverberations due to the acoustics of the Chamber. The reverberation can be approximated from the Eyring equation:

Here V is the volume of the room, S is its surface area, and a is the absorption coefficient of the room’s surfaces. The resulting value of T60 describes the time it takes for the sound pressure of the reverberation to decay by 60 dB, rendering it effectively inaudible.

From point #3 above, it follows that V = 2450 m3 and S = 1120 m2. The absorption coefficient a for stone walls is apparently 0.05 at all frequencies. Therefore, T60 = 6.82 seconds, indicating a very substantial reverberation of the kind that can only be produced in large rooms made of materials that reflect sound. This means that Ludlow’s fart would have reverberated for some time after it was released, and perhaps it is for this reason that it became so famous.

As an aside, much classical music was adapted to performance in cathedrals or other spaces that facilitated reverberation. Gregorian chant developed along these lines, as did the work of Bach. Modern religious musical styles, such as gospel, often have faster rhythms, and are therefore better adapted to smaller spaces.

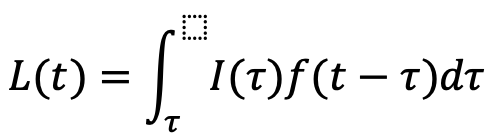

In any case, we can reconstruct a plausible version of the Ludlow fart by selecting a loud, smelly fart from our database, and adding the reverberations that would have been present in The House of Commons in 1607, using convolution reverb. For this we have:

This is the original fart f(t) convolved with the impulse response I taken from a room reverb simulator, which allows us to specify the location of the farter within the Chamber, as well as the position of the listener.

Here is an appropriate guess about how the original fart f(t) would have sounded. This fart was quite smelly (23.2 ppm VOC) and comprised of low sound frequencies:

Now, taking into account Ludlow’s position and the dimensions of the Chamber, here is how this fart would have sounded to someone sitting near Ludlow, at the “nether end of the house”:

And here is how it would have sounded to someone sitting at the opposite end of the Chamber from Ludlow:

Clearly this would have been a very salient fart, and it has been suggested that the poem it inspired was responsible for increasing tensions between the monarchy and the parliament. In fact, the final lines of the poem read, “Come come, quoth the King, libelling is not safe / Bury you the fart, I’le make the Epitaph”.