Question: What are the characteristics of smelly farts?

Short answer: They are loud and wet.

Long answer: Sensitive smellers fear the silent-but-deadly fart, but there is little evidence that such a fear is warranted. In the course of our experimental work we have recorded the smell and sound of over 1600 farts, so we can now tackle this question quantitatively.

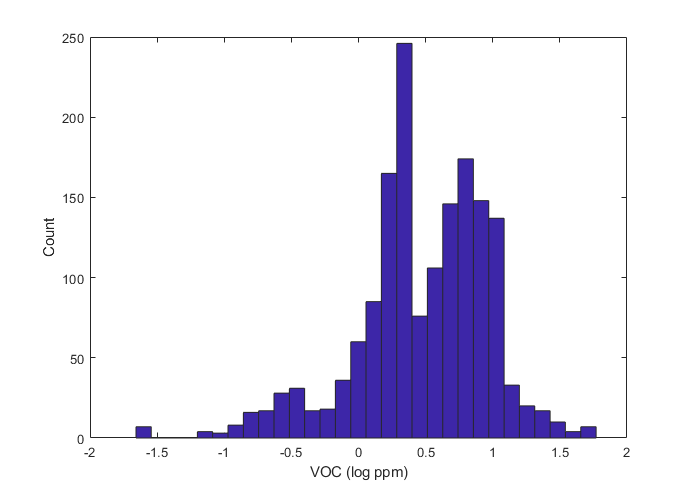

We measure the smelliness of farts in terms of the concentrations of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the air in the moments following a fart. There are many types of VOCs, but in terms of fart smelliness, hydrogen sulfide is likely the culprit (Suarez, Springfield, and Levitt, 1998). Using the custom equipment in our laboratory, we measure VOCs at a distance of 2 inches from the site of release. The figure below plots the distribution of peak VOC levels for the 1619 farts in our database. The data are shown on a log (base 10) scale to emphasize a key observation – there is a bimodal distribution of smelliness, with one mode occurring at around 0.25 (or 1.78 ppm) and another at around 0.75 (5.6 ppm).

So what are the differences between Type I and Type II farts? Analysis of the two modes indicates two main differences. Type II farts (the smellier group) are on average 16.7% louder, and this represents a statistically significant different (t-test, p < 0.0003). They are also 41% wetter, as indicated by the humidity gauge located within our experimental rig (p < 0.0004): Type II farts increase humidity by 4.4%, while Type I farts only increase it by 3.2%. Other measures based on sound frequency, duration, temperature, etc. showed no significant differences.

Related question: Do all farts smell bad?

Short answer: No.

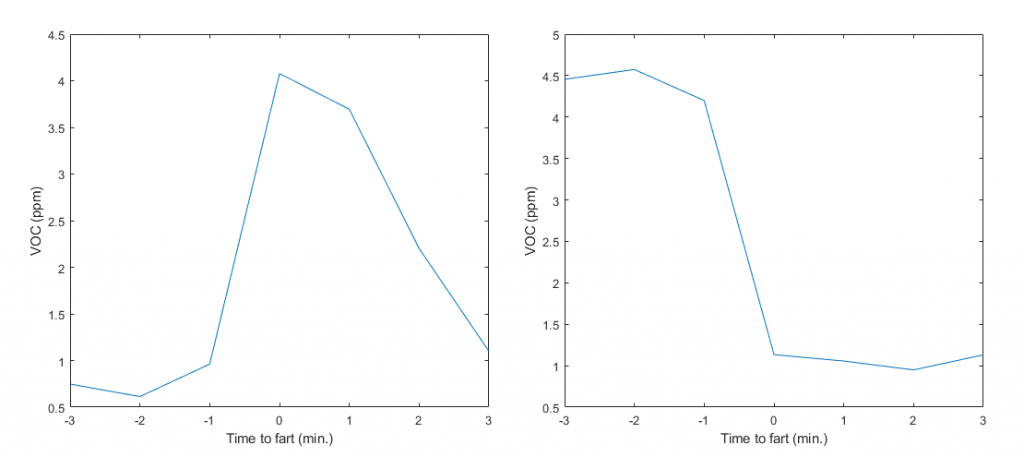

Long answer: Also apparent in the figure above is a hint of a third mode near -0.5 (0.3 ppm). A surprising fact about these Type 0 farts is that many of them actually improve the quality of the air. In our data, the typical fart causes an immediate elevation in VOCs that lasts for several minutes, as can be seen in the figure on the left below; this represents the average time-course of all Type I and Type II farts. In contrast, many farts cause an immediate drop in VOC concentration, which also lasts for several minutes (see figure below on the right). One of the members of the College has coined the term “air-purifying farts” to describe them.

Of course, this is perhaps something of a misnomer, since the air-purifying farts clearly occur against a baseline of very poor air quality, in which the typical concentration of VOCs is around 4.5 ppm. This figure almost certainly reflects the lingering miasma of previous farts, an unavoidable problem in our laboratory. Indeed, air-purifying farts comprise 11.9% of all farts, a substantial fraction.

That said, it is a fact that farts consist overwhelmingly of air, with the smellier compounds comprising less than 1% of the volume. So it is entirely possible that someone with relatively innocuous-smelling farts, who enters a poorly ventilated environment, could actually improve the quality of the air by means of flatulence. After all, the human olfactory system adapts quite quickly to odors, so that it is often more sensitive to changes in odors than to the odors themselves.