Question: Is the human ear particularly attuned to fart sounds?

Short answer: Yes.

Long answer: As we have previously discussed in some detail, farts have a unique sound signature, comprised of a concentration of power in the range of about 200 – 500 Hz. This is the basis of our Flatus Reflector technology, an algorithm that detects farts in sound clips.

We suspect that this common feature of farts is what allows our artificial intelligence algorithm, FartNet, to discriminate between fart and non-fart sounds with such high accuracy. FartNet is a neural network that learns to extract the common features of farts through exposure to databases of different sounds.

Of course, the human brain is a kind of neural network, and it is constantly exposed to fart sounds. The average person probably hears about 10 – 20 of their own farts per day, as well as the farts of people around them. Thus, by the time a child has reached the age of 18, they have probably heard more than 100,000 farts. This raises the obvious question of whether the human auditory system has particular sensitivity to fart sounds.

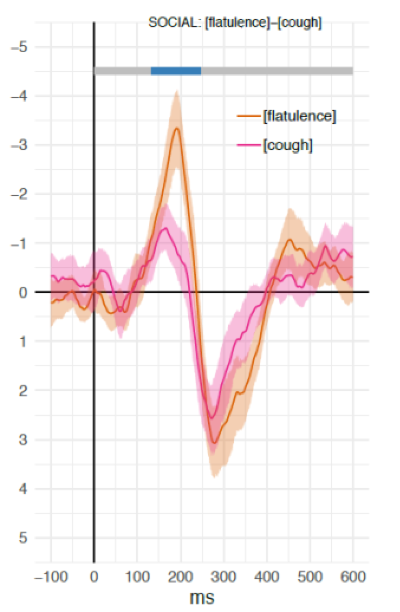

Groundbreaking work by Petrosino et al. (2021) suggests an affirmative answer. These researchers measured human electroencephalogram (EEG) activity in response to recordings of different kinds of sounds. From the resulting data, they recovered the mismatch negativity, a standard measure of the extent to which the brain’s response to sensory stimuli is affected by expectations. Petrosino et al. found that the amplitude of the mismatch negativity was greater for fart sounds than for a similar biological sound (a cough), suggesting a particular valence for fart sounds.

To determine whether farts really have special perceptual significance, we conducted an experiment in which subjects were asked to detect sounds masked by auditory noise. In one block of trials, people were asked to detect the following fart sound:

When the fart was masked by noise, it sounded like this:

We compared detection performance to that of a similar task, in which subjects were asked to detect a different sound, namely a piece of metal being dropped on the floor.

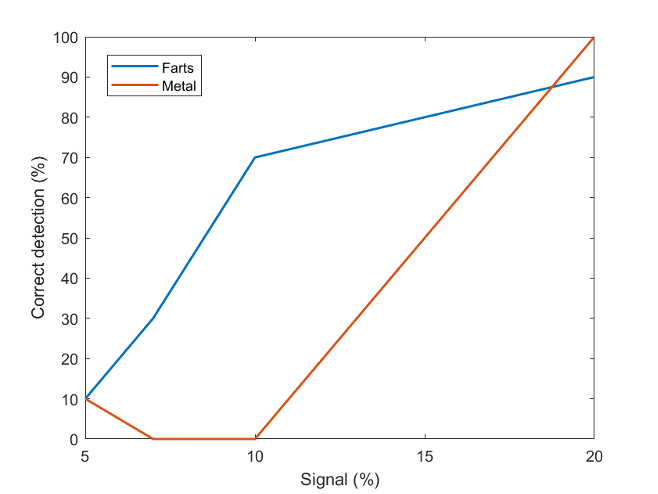

We chose this sound because it is acoustically similar to farts. The amplitudes of the two sounds were normalized to the same values, so that they were objectively equally detectable. Here are the resulting psychometric functions:

Correct detection of fart sounds was possible with around 7% signal, meaning that more than 90% of the stimulus was noise. Meanwhile, the threshold for detecting the metal sound was 15% signal, suggesting that people are about twice as sensitive to fart sounds as to other sounds, even when they are acoustically similar to farts. Interestingly, false alarms, in which people reported hearing a fart sound in pure noise, were more common for the fart sound than for the metal sound (9% vs. 2%). Thus, people tend to hallucinate fart sounds when listening to noise. This may again be due to experience, as we have previously shown that about 5% of non-fart sounds actually sound like farts.

These results therefore indicate that, even at the outer limits of perception, people retain a high degree of sensitivity to fart sounds. Combined with similar findings regarding fart smell, our data demonstrate that the human brain is inordinately sensitive to farts.