Question: Are quiet farts really the smelliest?

Short answer: No.

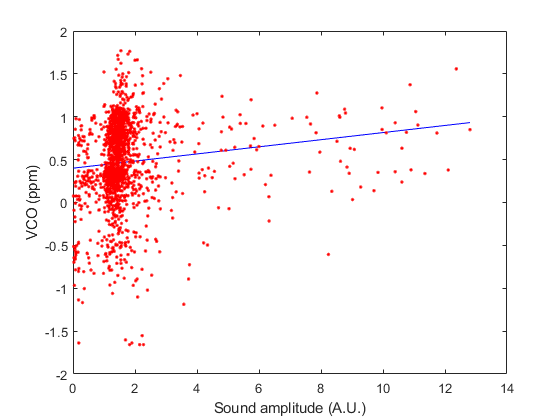

Long answer: A common belief is that quiet farts are particularly smelly, but we could find little evidence for this idea in the flatological literature. In our data sample, we did not record any truly silent farts, but there was a large range of loudness, and so we initially formulated the question in terms of a relationship between sound amplitude and smelliness. The silent-but-deadly (SBD) hypothesis would predict a negative correlation, but as mentioned in another post, the relationship is, if anything, likely to be a positive one. Below is a plot that directly illustrates the sound amplitude and log VOC count (i.e. smelliness) of 1619 farts. The overall trend suggests a positive correlation, with louder farts being a bit smellier, and indeed this correlation is statistically significant (linear regression, p <0.000005). Of course, the R2 here is only 0.0155, so it’s a weak correlation. But the point is that there is no evidence that quieter farts are smellier.

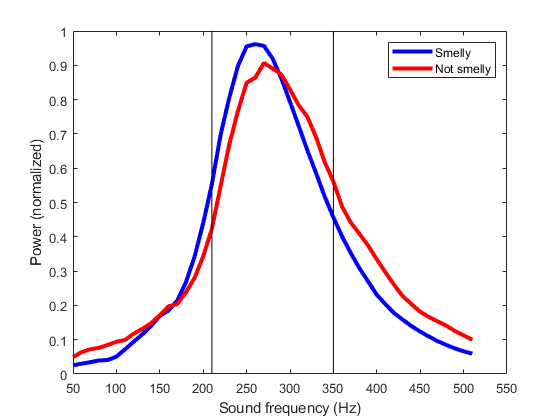

Further analysis suggests another interpretation of the SBD that might be more viable, though it requires a bit more explanation. The starting point is the observation that smelly farts have somewhat different sound frequencies than non-smelly farts. Plotted below are the mean normalized Fourier power spectra for the smelliest 10% of all farts (blue) and the least smelly 10% (red). Although they are fairly similar, the smellier farts tend to have more power at low frequencies and less power at high frequencies.

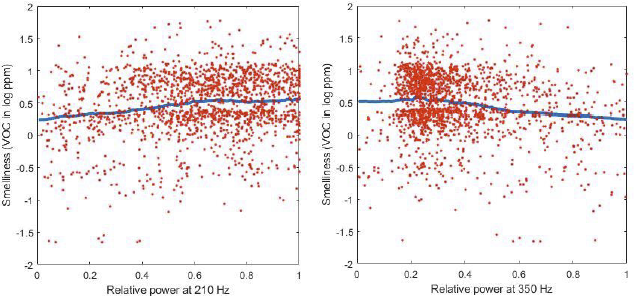

Indeed, if we consider the relative power at a frequency of 210 Hz, we find a reasonable positive correlation with smelliness, as shown in the plot below on the left. And there is a negative correlation between relative power at 350 Hz and smelliness, which is shown in the plot on the right.

So the bottom line is that if you hear a fart with a low-frequency rumble, you can expect the smell to be pretty bad. The more high-pitched the sound, the more tolerable the air quality will be.

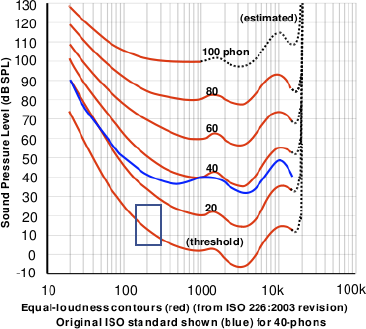

But what does any of this have to do with the silent-but-deadly phenomenon? The answer is that human hearing is not very sensitive to low frequencies. Unsurprisingly, it seems to be most sensitive to speech sounds, which are typically in the kHz range. More generally, the sensitivity of human hearing can be described by Equal-loudness contours like the one below. These are a bit complicated, but they are meant to capture the conditions under which two sounds would be perceived as equally loud by a young person with normal hearing. The red lines show that, to maintain the same perceived loudness, low frequency sounds have to be physically louder than high-frequency sounds, across a range of frequencies up to about 1000 Hz. Moreover, the disadvantage for low frequencies is worse when both sounds are relatively quiet, as indicated by the steep curve on the bottom (labelled “threshold”).

Thus a quiet, smelly fart, with its low frequency content, will be hard to hear. A non-smelly fart, even if it is physically exactly as loud, will be perceived as louder. Indeed, our calculations show that the frequencies around 200 Hz, which are common in stinkier farts, would have to be 274% louder than the olfactorily innocuous frequencies around 350 Hz, for the two sounds to be perceived as being equally loud. As a result, the lower frequencies in quiet, smelly farts might very well slip below auditory threshold, and in this sense, they would be silent but deadly. But a loud, low-frequency fart is still your best bet to clear the room.